April 12 2010 (Reviewed July 16,2021)

eCoaching Tip 76 Feedback in Discussion Posts – How Soon, How Much and Wrapping Up

When do your students want feedback? When it is good to give feedback? What are the three most important purposes of feedback? These are some of the questions that faculty ask when getting together as they did in a live webinar in April of 2010.

Most Pressing Question about Feedback

The most pressing questions often revolve around how and when to provide feedback in the discussion postings. Student feedback suggest that this is a course area that students in general desire more feedback on earlier and more frequently. At the same time this is an area where striking an appropriate balance can be tough. Some faculty shared that they feel that jumping in too early with feedback “dominates and skews the dialogue.” Other faculty share that it is hard to know just what to say when. There was general agreement that the goal is to achieve a balance between too much and too little feedback while also balancing when to provide one’s “expert” presence in the discussion forums. We know that we want to provide enough time for reflecting and thinking early in the week’s postings so that learners can really think through what they think and why. Everyone agreed that we miss the opportunity to simply “nod our heads” or say “keep going” or simply “good” and then invite another to comment, as we can when we are face-to-face. Maybe we can figure out how to do this virtually.

After much discussion faculty consensus suggested a cycle of feedback that corresponds to key time points in a discussion posting. This cycle is described in the next section. See what you think about this approach and how it might work for you.

One Scenario of a Feedback Cycle for a Discussion Forum

In the early part of a discussion cycle, simple acknowledgements let the students know you are present and that you are aware of what thinking and sharing is going on. This can mean feedback such as, “Scott, thanks for getting us started this week.” Or “Christina, thanks for stating your position so clearly. You might also think about extending your thinking to a similar, or related pattern in X’s thinking.” Or “Andrew, keep thinking along these lines. Also, you might comment about how this experience might relate to Scott’s thinking.”

In the early days of a discussion posting you want to find ways to let your students know that you are listening; that you are considering their questions or difficulties that they may be having in completing the readings or the postings. Supporting comments let them know that you are sharing their learning experiences.

As the week progresses, possibly in days three to four, your feedback might expand to encourage your students to be listening to each other, and to note similarities or contrasts in their thinking or the experiences of others. Your feedback at this point is to gently channel or shape the learner’s thinking and their expression of that thinking. Remember that it is often effective to include requirements in your rubrics for learners to provide feedback to one another on their thinking. This helps to create a participatory sustained conversation, rather than just turn-taking of isolated unrelated postings. This point in the discussion forum cycle is a good time to question, challenge, and suggest. It can be a good time to suggest paying attention to patterns within a concept with a link to a current happening or event.

Many faculty in the webinar seemed to agree that the practice of providing significant “expert” feedback is best done later in the week. At the same time, it is important not to wait so long that the expert feedback does not shape and channel thinking. Students need time for reflecting and integrating core concepts and significant groundings. Remember, it is the learner who must be doing the work of thinking and integrating and there must be time for this.

Feedback to Wrap Up a Discussion Forum

The last part of the discussion forum often includes a posting from the faculty member in his/her role as the course expert and facilitator. This post serves two purposes. First, it serves to ‘wrap up” and summarize the thinking and ideas generated by the group as a whole. In some courses this discussion wrap can be done by students either individually or as a team of two. Or each student can post a “thought thread” or “thought nugget” that they are taking forward. The second purpose of a course wrap, often best done by the faculty member, is to provide a transition to the next module and to the next learning tasks.

Value of Rubrics for Feedback

A related topic on feedback for discussion postings is rubrics. Faculty generally agreed that rubrics are very efficient and effective. While rubrics can initially take a little time to develop, they can then be readily modified for other assignments.

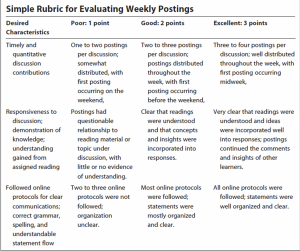

It is hard to overstate the value of rubrics (1) in codifying the criteria and standards for an assignment thus making grading easier; (2) in communicating the academic and professional expectations of an assignment or project, and (3) providing a tool for self-review and peer-review. Rubrics can range from a simple three-point rubric for discussion postings to more complex rubrics for projects and for emphasizing specific skills such as critical or innovative thinking.

A simple rubric from Boettcher & Conrad, 2010 for getting you started in using one for discussion posts follows:

Simple Rubric eCoaching Tip 76

As a quick reminder, a rubric is a scoring system that is usually set up as a matrix with the two or three desired characteristics in the left-most column and a three-point scale for each of those desired characteristics in the next set of three columns. In the example here, the rubric includes measures of time (when and how often postings are posted), quantity (a length appropriate to the discussion topic), and content (resource related, thoughtful, and substantive) that factor into the points earned.

Another measure often used in rubrics is format, which includes adherence to appropriate written English. In our discussion many faculty commented on the need to provide feedback on what is basically professional writing standards and accuracy. This is such a fundamental professional skill that it might be worth some coordinated action to address. Links to other rubrics, such as for podcasting and blog entries are in eCoaching tip #75.

Three Purposes of Feedback

It is tempting to think of feedback in the context of assessing or grading. However, the purpose of feedback is more multidimensional. In fact, the goal of feedback is to help learners grow in their knowledge, in their expertise, and is thus forward-looking. Here is a three-point summary of the purposes of feedback.

- Convey the sense of caring, relationship support and “being there”

- Guide the development of skill, knowledge

- Guide metacognitive and life-long learning competencies

In our discussion of the need to provide feedback on professional writing standards Jim Wolford-Ulrich (Duquesne University) suggested mapping feedback on students’ writing to these three purposes. Providing feedback on what is standard written English shows that you care about and wish to support the student’s professional competency. Secondly by encouraging self-assessment and peer review faculty can help guide a student’s development as a skilled writer. By providing resources for good writing and keeping expectations high, faculty can encourage awareness and life-long competency in writing.

Conclusion

Thanks to all the faculty who participated and shared their thoughts and insights on feedback. A special thanks to G. K. Cunningham who teaches the Intro to Grad Study in Leadership and Mona Shields, who is teaching a course on building effective teams this spring for sharing their effective practices.

Selected References

Boettcher, J. V. E-Coaching Tips E-Coaching Tip 59 (#1 Summer 2008) “Are You Reading My Postings? Do you Know Who I am?” Simple Rules about Feedback in Online Learning. Retrieved April 8, 2010 from http://www.designingforlearning.info/services/writing/ecoach/tips/tip59.html

Ericsson, Anders K.; Prietula, Michael J.; Cokely, Edward T. (2007). The Making of an expert. Harvard Business Review (July–August 2007). Retrieved March 22, 2010 from http://www.coachingmanagement.nl/The Making of an Expert.pdf Excellent focused article providing summary of expertise and what It means for teaching and learning.

Mory, E. H. (2004). Feedback Research Revisited. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (2 ed., pp. 745 – 784). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Mahwah, NJ. Comprehensive summary of feedback research. Well-organized discussion of the many variables and uses of feedback in learning, such as such as information load, timing, and types of outcomes being studied. Retrieved March 22, 2010 from http://www.aect.org/edtech/29.pd

Razmov, V. N. (2007). Effective Feedback Approaches to Support Engineering Instruction and Training in Project Settings. Paper presented at the 37th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, Milwaukee WI. http://archive.fie-conference.org/fie2007/papers/1666.pdf

Wolford-Ulrich, J. Resources on Giving and Receiving Feedback. A Supplement to the Brown-Bag Lunch Presentation Given at USIS on 22 July 2008. http://www.inflectionpoints.com/usis

Note: These E-coaching tips were initially developed for faculty in the School of Leadership & Professional Advancement at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, PA. This library of tips has been organized and updated through 2021 in the third edition of the book, The Online Teaching Survival Guide: Simple and Practical Pedagogical Tips coauthored with Rita Marie Conrad. Judith can be reached judith followed by designingforlearning.org.

Copyright Judith V. Boettcher 2010-2021