March 16 2009; Checked April 23 2020

eCoaching Tip 64 Three Best Practices in Assessment

Our tips for this spring (2009) have focused on important basics of online learning, spiced up with a few new ideas. This tip reviews three of many possible best practices in assessing student learning.

These practices range from simple recall to more complex knowledge creation. They build on some of the “Designing by 3s” strategies from the eCoaching Tip 63 Design Practices for Quality Course Experiences — Designing by Three’s.

Experienced online faculty might be particularly interested in the ideas on expanding student choices for course projects. These choices can include creating videos, podcasts, webinars, talk show interviews, wikis and blogs.

Best Practice Assessment 1: Assess across the six levels of cognitive skills of Bloom’s Taxonomy

This best practice extends the “Design by 3” practice of assessing at three levels: (1) facts and concepts; (2) simple “doing” applications; and (3) more complex “creation” projects. For example, these three levels are readily discernible in a course in math or biology. The first level of facts and concepts requires learning core vocabulary, concepts and discovery stories; the second level generally includes hands-on exercises with relatively simple problems; and the third level is grappling with more complex problems, even including those problems with no known answers.

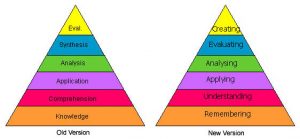

Bloom’s 1956 taxonomy and the updated version by Krathwohl in 2002 each has six levels of cognitive processing. One important difference between the two taxonomies is that Krathwohl’s updated taxonomy uses verbs rather than nouns to indicate the type of cognitive processing going on. A second difference is that the top level in the updated taxonomy is creating, rather than evaluating. As we all enjoy the creative processes and usually the results of that creative process, this is a fitting top-level experience.

The updated taxonomy is illustrated in the pyramid figure below. The two foundation processes, (1) remembering and (2) understanding might be compared to the assessing of facts and concepts. The middle two processes of (3) applying and (4) analyzing might be compared to the simple “doing” applications, which includes manipulating and working with content. The two top processes, (5) evaluating and (6) creating are processes involved when learners are planning and creating complex objects or course projects. These processes are also in play when learners review the work of peers and respond with critiques or commentary.

The pyramid figure that names the six core cognitive processes also serves as a good reminder that acquiring new skills requires a series of steps; and each step involves developing links or making changes to our existing knowledge base. You might want to print a copy of this pyramid and place in your office somewhere, or on your desktop as an icon.

Bloom’s Taxonomy updated by Krathwohl, 2002.

How can you effectively assess the range of Bloom’s taxonomy? Here are a few strategies.

Assess facts and concepts:

- Use the quiz function for basic vocabulary, discipline-specific seminal facts, concepts, ideas, quotes, story lore or biographies. Story lore can be part of learning the when, where, how and why a story became part of a discipline’s history. Remember that quizzes are best used for practice, recall and building a common cultural and knowledge base. Consider soliciting questions from each group of students or having a Jeopardy-like game context. Grading of these quizzes is simply by completion; extra points might be given for submitting great, innovative, or thoughtful questions or being among the first set of students to complete a quiz successfully.

- Develop a discussion forum assignment that encourages integration of basic content knowledge with existing knowledge. One strategy that can encourage this type of thinking is to ask students why and how they know content or concepts and how they have used or will use the information in the future.

Assess with simple “doing” tasks

- Students do enjoy “doing” rather than just listening, reading or watching content resources. So short assignments can be very effective and can be assessed with simple rubrics and guidelines. Examples of short assignments include evaluating web sites, doing research to find similar, alternative or comparative content ideas, preparing short reports/news reports, podcasts, or short blogs. These short assignments can include elements such as sharing the tracking of how ideas evolve and identifying links with others’ ideas. These types of assignments require students to analyze, categorize ideas and detect relationships and patterns. These are all examples of good middle layer assessment activities.

- Individuals or small teams can also create graphical representations of important processes and then “explain” the processes with current examples or objects.

Assess with complex “creating” projects

- This level of assessment continues the theme that students enjoy “hands-on” activities that often include interaction with others. (But not necessarily so.) A major part of an online course grade is often a course project. Other ecoaching tips have encouraged designing course project requirements that can be personalized, and customized. These projects often have a minimum of three phases or points of review and assessment. The first milestone is usually a proposal followed by a detailed plan or completed section, and the final project and presentation. Of course, projects can be designed as individual, team or group projects with appropriate modifications. Course projects are examples of the higher level of evaluating and creating activities.

- Most course projects follow a traditional pattern of either a paper or a report of some type. Today’s students might enjoy branching out from these traditional projects to create radio, television or Internet news shows, interviews, short presentations such as webinars, or lasting contributions to Wikipedia or course resource databases. If you have an extra few minutes, explore the kinds of film projects that students create in the Campus MovieFestival. This project was started in 2000 and since then, many thousands of students have ‘told their stories” via the big screen, learning movie-making skills such as writing, editing, and filming with current software and technology tools.

- Higher-level assessment projects generally require more sophisticated assessment rubrics. Providing the rubrics in advance enable learners to self-assess and peer-review along the creative path. The rubrics also serve to remove some of the subjectivity out of the final grading. This is particularly useful as projects tend to be more personalized and customized.

Best Practice in Assessment 2: Assess the core concepts in your course

This best practice requires thoughtful analysis of the course content as you are planning your course. Learners will only learn and take away a limited amount of knowledge and skill from your course. Determining what those core concepts are and then relentlessly focusing on those core concepts from multiple perspectives is what drives student’s acquisition of core concepts. Sometimes this work has been done for you by textbook publishers and are captured in the course performance goals. Reviewing just what those core concepts are and how the course experiences and requirements assist the learners in achieving those is part of the assessment design process.

See if you can answer these three questions.

- What are the four, five, or ten core concepts to which you can link everything else in your course? Can you build a concept map linking these core concepts and differentiate concepts from methods, procedures and categories. Concepts will serve as a frame for your domain of knowledge.

- How do the course experiences assist the learners in making those core concepts their own and integrating them into their knowledge base?

- What assessment tools will you use to gather evidence of your students’ grasp and understanding of those concepts?

Best Practice in Assessment 3: Help students succeed on assessment tasks

This is best practice #8 from the set of best practices Best Practices in Assessment: Top Ten Recommendations (p. 4) of the American Psychological Association (APA).This best practice reminds us of the value to students of (1) explicit expectations; (2) detailed instructions; and (3) samples and models of successful performance for the assessment activities. This best practice also encourages providing opportunities for practice and detailed feedback. In other words, the best assessment is ongoing, and embedded into the learning experiences with no surprises. This means rubrics, feedback with multiple reviews (self, peer and expert). We want our learners to succeed.

Classic Resources on Assessment

Here is a short set of annotated resources on assessing student learning that you may want to explore.

- This website Assessment Commons is probably best described as the granddaddy of all assessment resources on the net. It has gone through many iterations, but now currently contains about 1,500 links, including about 500 college and university assessment sites.

- The most cited list of assessment principles is 9 Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning. These principles were developed in 1991 under the auspices of the AAHE Assessment Forum with support from the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education. Authors of the principles include Alexander W. Astin, Trudy W. Banta, K. Patricia Cross, Elaine El-Khawas, Peter T. Ewell, Pat Hutchings, Theodore J. Marchese, Kay M. McClenney, Marcia Mentkowski, Margaret A. Miller, E. Thomas Moran, and Barbara D. Wright.

Note: These assessment principles often combine principles assessing individual student learning within a course with principles assessing the learning of student cohorts. The set of best practices listed next is a good complement to this set.

- This site – The Assessment CyberGuide for Learning Goals and Outcomes—is part of the APA professional site. A brief listing of Best Practices in Assessment: Top 10 Task Force Recommendationsis on p. 4 of this guide.

References

Astin, A. W., Banta, T. W., Cross, K. P., El-Khawas, E., Ewell;, P. T., Hutchings, P., . . . Wright, B. D. (2012). 9 Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning. Retrieved from https://www.apu.edu/live_data/files/333/aahe_9_principles_of_good_practice_for_assessing_students.pdfs

Bloom, B. S. and Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain. Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

Forehand, M. (2005). Bloom’s Taxonomy. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching, and Technology (Vol. 2010). Retrieved from http://epltt.coe.uga.edu/index.php?title=Bloom%27s_Taxonomy

Hutchings, P., Ewell, P., & Banta, T. (2012). AAHE principles of good practice: Aging nicely. . Retrieved from https://www.learningoutcomesassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Viewpoint-Hutchings-EwellBanta.pdf

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218. Retrieved from https://www.depauw.edu/files/resources/krathwohl.pdf

Overbaugh, R. C., & Schultz, L. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Retrieved from https://www.odu.edu/content/dam/odu/col-dept/teaching-learning/docs/blooms-taxonomy-handout.pdf

Pusateri, T., Halonen, J., Hill, B., & McCarthy, M. (2009). The assessment cyberguide for learning goals and outcomes. Retrieved from Washington DC: http://www.apa.org/ed/governance/bea/assessment-cyberguide-v2.pdf

Smythe, K., & Halonen, J. (2009). Using the New Bloom’s Taxonomy to Design Meaningful Learning Assessments. Retrieved from https://content.dodea.edu/VS/csieportfolio_14/docs/Cognitive_Taxonomy_Circle.pdf

Note: These eCoaching tips were initially developed for faculty in the School of Leadership & Professional Advancement at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, PA. This library of tips has been organized, expanded and updated in the second edition of the book, The Online Teaching Survival Guide: Simple and Practical Pedagogical Tips (2016) coauthored with Rita- Marie Conrad. Judith can be reached at judith followed by designingforlearning.org.

Copyright Judith V. Boettcher, 2006 – 2020